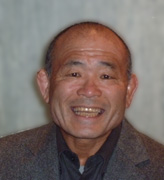

Judo in the words of Isao Okano-Sensei

In late January, I asked Mr. Isao Okano for his thoughts on today’s judo. It hardly needs saying that Okano-Sensei was Gold Medalist in the middle-weight category at the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, as well as two-time winner of the All-Japan Judo Championships (still holding the record for lightest-weight champion). Having also won the 1965 World Judo Championships (middle-weight category), he is one of the very few in Japan to hold the triple crown of Olympic, All-Japan and World titles. He presently holds no official post in Japanese judo circles, but his skills and his unwavering stance toward upholding the fundamentals of judo command respect both at home and abroad.

Though he has just turned 67, Mr. Okano still gets into his judogi and takes his place on the tatami mat in an on-going career that, including his position at Ryutsu Keizai University, involves judo instruction both in Japan and overseas. He carries a mettle that says, “I can’t just stand by and watch judo turning into a sham.” Each of his statements below bears important points relating to the essence of judo.

( February, 2011 Edited by Gotaro Ogawa)

1. “Looseness” in the fit of judogi

For some time, I have felt there is something wrong with today’s judogi.

It is because when you get into them, you don’t get a feeling of “looseness” or “roominess.” To give one example, when I’m giving lessons on Seoinage, I can’t even maneuver my wrist grabbing my opponent’s collar because there isn’t enough room, and that shouldn’t be. If things go on this way, we’ll no longer be able to use this most basic of judo techniques, and it will be impossible to practice real judo. The difference between combative sports like sambo, sumo and Iran’s wrestling as compared with judo comes in what you wear. The outfits make a big difference in what kind of techniques you can use.

Judogi had their origins in the Japanese kimono, and because kimono are loose-fitting, this made it possible to execute a wide range of techniques, and that led to judo’s distinctive “Sho yoku dai wo seisu (small can conquer large)” character. The outfit formerly used in jujitsu was relatively close fitting, but modern-day judo brought in judogi with a fuller, looser fit.

When judogi don’t have the necessary looseness, it kills the unique nature of judo, and judo begins looking like other combative sports, one result being that you lose the interest and attraction of open-weight matches. Speaking of matches, one thing we need is to have pre-match checks, inserting the hand to see whether the athletes’ judogi are loose enough.

2. Ban on use of the hand in direct attacks below the obi

I myself haven’t gone to see many international tournaments so don’t have an accurate grasp of how the new rules banning hand attacks below the obi are actually being applied. But when I heard of these new rules, I felt concerned that they would make it difficult to use “Go no sen (to make a delayed offensive move taking advantage of the opponent’s attack)” and would reduce the interest of open-weight matches.

There are two main approaches to taking “Go no sen.” One is to use your opponent’s technique and turn it on himself. The other is to absorb it and turn to applying one of the techniques you yourself are good at. I got the impression that under the new rules, we’d no longer be able to use techniques like the Sutemi Kouchigari, Kataguruma, or Ouchigari with a hold on the leg, and that it would be hard to execute Sukuinage or techniques where you hold your opponent around the waist and throw. In that case, it would put an end to “small can conquer large” open-weight category matches. I thought that at the very least, there must be a way to designate just a bare minimum of techniques to be banned.

Only, later on, when I went to the United States and watched practice and matches there, I noticed that under the new rules, a good number of judoka were not aiming for the legs but instead working harder to master fundamental judo techniques like the Uchimata, Taiotoshi and Seoinage. It was good to see judo becoming more authentic, but in another way, I felt there were fewer techniques showing originality and that offensive and defensive interactions had become simple and less interesting.

I want to keep a close watch on how these new rules develop.

3. Newaza

Newaza are essential to judo. Gaining skill in Newaza depends on how you use your legs and requires hard training in using all four limbs, both arms and both legs. Many of today’s judo athletes don’t know of these fundamentals.

When you watch Newaza in matches these days, you find a tendency to lie face down on the mat waiting for the referee to help you out with a “Mate” call. With tactics like this, Newaza are as good as dead. Turning your back on your opponent means getting attacked from behind, and that kind of tactic has no place in the martial arts. You have to lie face up and spar. Shouldn’t they be considering laying penalties on athletes so passive as to lie face down waiting for help from the referee? That would be one way to get Newaza back to the position it deserves.

There are also problems with the referees. Referees don’t know enough about the process of Newaza, so they have a strong tendency to make the two opponents return prematurely to their feet. If they had a good knowledge of the unfolding process involved in attacking and defending in Newaza, they would know whether it’s coming to a standstill or not. There are all too many referees who don’t know much about it, or who have only shallow experience. There’s a need to stop giving refereeing positions to people like that. While on referees, to make another point, it’s really regrettable how many times in international matches you find techniques unqualified as Ippon being declared, nevertheless, as Ippon. There is a clear need for the training and drilling of referees.

4. Riner’s manners

Last September in Tokyo at the open-weight category finals of the World Judo Championships, when France’s Teddy Riner lost by decision, it was reported that he was dissatisfied with the referees’ decision and left the mat without giving the “rei” bow. I wasn’t there to see it in person, but if the media reports are correct, it is a serious problem. Judo begins and ends with “rei.” You might have lost or disagreed with the decision, but leaving without “rei” is the same as starting a brawl.Down through the years, judo in France has been taught as judo should be, so it is my expectation that this incident has not been overlooked. It would be strange if those in French judo circles did not caution Riner or serve him with a penalty, and could lower France’s reputation. Japan herself should have given a warning on this matter. Many young people and children learning judo here in Japan were watching through television and other broadcasts. “Judo Renaissance” has been emphasizing manners and respect. Japan should have lodged a protest. If Japan is weak at voicing her opinions on an international level, then she should join with France and speak out on this subject.